Kostro and Annie: An unlove song (La chanson du Mal-Aimé)

Some of us are better at being dumped than others

When Apollinaire was a twenty-one-year-old still going by the name Wilhelm de Kostrowitzky, he was hired as a French tutor for a well-to-do German aristocratic family. They took both him and their children’s governess, a young Englishwoman named Annie Playden, along on a holiday to the Rhineland. There, “Kostro” and Playden had a fling. He fell roaringly in love with her, but she turned down his mountaintop offer of marriage. Rather than romantic, she found the view frightening, as it was on a cliff’s edge. And when he arrived, uninvited, to propose to her again in London, at the house in Clapham where she lived with her parents, he shouted and pounded on her door and in his desperation threatened to break it down. To get rid of him once and for all, she told him she was moving to America. Then she decided she must go through with it, moved to America, and vanished from his life.

Today, of course, she’d file for a restraining order. Who could blame her?Apollinaire was, besides a genius, an alcoholic brute. (This later lost him another great love, the painter Marie Laurencin.) Furthermore, Playden was a sensible English girl, and Kostrowitzky was a tempestuous, dark-haired pan-European of dodgy origins whom she’d kissed while working abroad. And besides, if she had been a fool and married him, we would not have this grand poem.

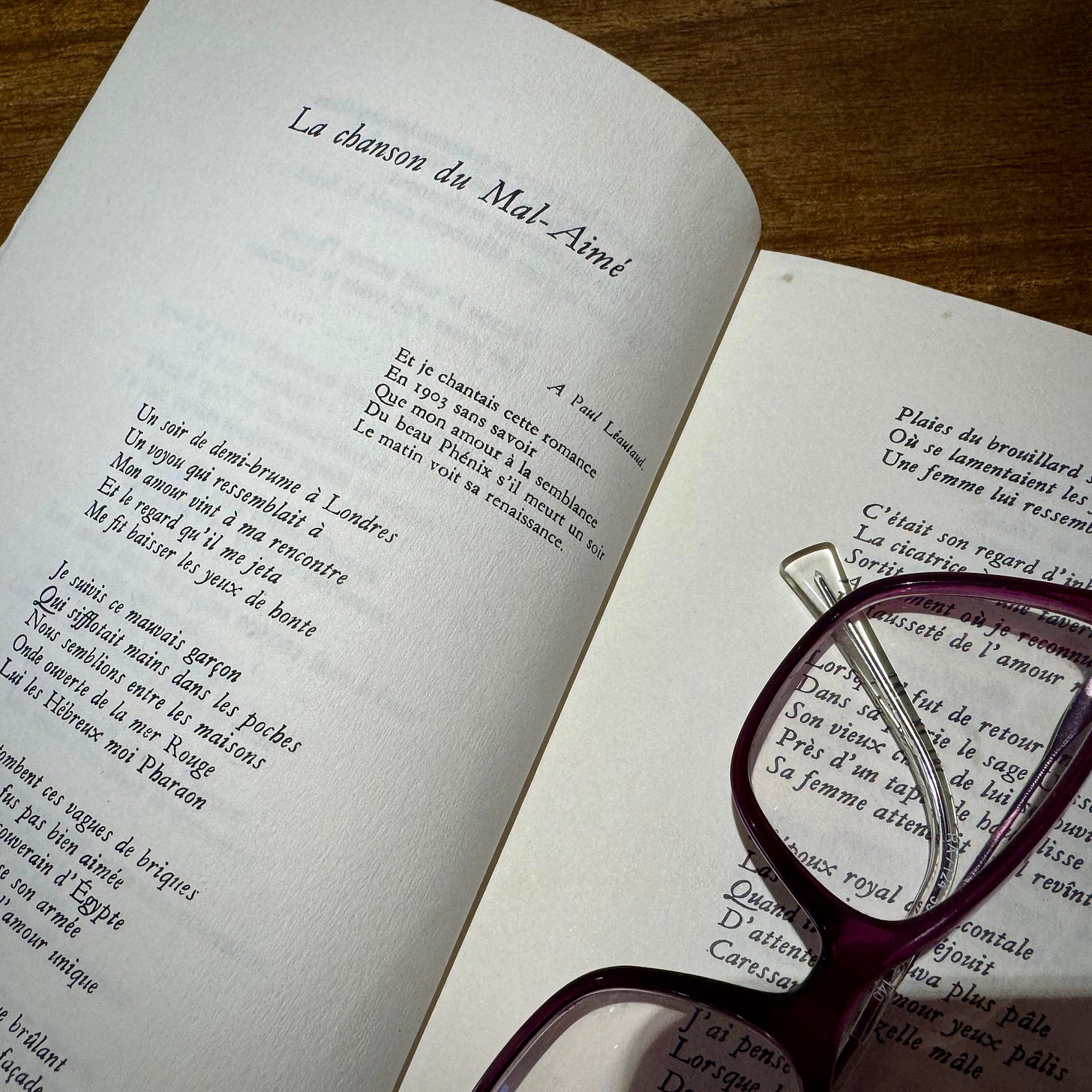

“The Song of the Unloved”1 (“La chanson du Mal-Aimé”) was initially published in 1909 in the Mercure de France, with the support of its theatre critic Paul Léautaud, and then published in its final version in Apollinaire’s collection Alcohols (Alcools) in 1913.

In the first section, the narrator wanders through London at night and sees a man and a woman who both remind him of his love. This sets him upon a reverie that carries him through recollections of passion and heartbreak, classical allusions, religious motifs, and historical incident, until the final section ends back in Paris.

The poem is set in A-B-A-B-A rhyming stanzas. The main sections of the poem appear in italics. Three interludes in plain type act as texts quoted within the larger text. The first is presented as a song sung in the past by the narrator; the second a very rude letter to the sultan of the Ottoman Empire; and the third a catalog of invented legendary medieval swords.

Because I have done these translations to foster a wider appreciation in English of Apollinaire, I am making them free to read. However, if you would like to support my work with a paid subscription, I wouldn’t dream of stopping you.

You can find the full original poem in French here.

Mal-aimé is often translated into English as “poorly loved” or “ill loved.” Because it is the opposite of bien-aimé (beloved), I translate it as “unloved.”