I know it's April, but bear with me: Sick Autumn (Automne malade)

Poetry is your trenchcoat for the transitional seasons

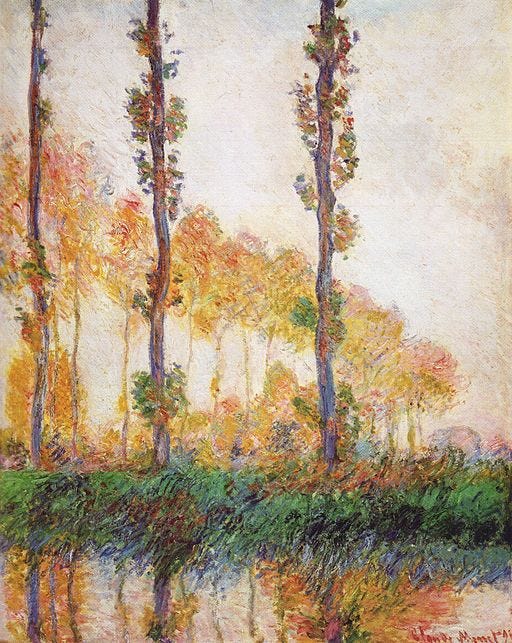

In paintings, autumn is almost always nice. Rare is the painter who can resist an ogle at a crimson tree. I remember, in New York, the arboreal annual riot, all Central Park bursting into a kind of Biblical flame that does not consume. But what am I saying? It did consume—we had only a week or two to gorge upon the spectacle, and then there was a trampled, damp carpet of carnival-colored shreds on soil and sidewalk, and then rake, sweep, and rot, brown and black leafmould, followed by stark winter, bled of all color, as styled by some celestial Chanel—black and gray, until you think you’ll die of ocular starvation before the cold gets you.

I grew up in California where autumn is not a thing. Our climate was what is Eurocentrically known as Mediterranean, and our redwoods were evergreen. The deciduous trees had their moment, but it was, so far as I remember, a dry brown moment, not a flamboyant one. The world did not catch fire so much as gently toast. So all reflections on autumn that did not involve lusting after cordovan back-to-school loafers in the Sears catalog were not relevant to my interests, until New York.

But enough about me. Let me quote some dead poets.

In 1819, John Keats’s Autumn was all about harvest, abundance, ripeness:

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.But then in 1859, Charles Baudelaire was reaching for his cardigan and woolen socks while grumbling:

Bientôt nous plongerons dans les froides ténèbres; Adieu, vive clarté de nos étés trop courts!

Literal translation: Soon we will plunge into the chilly darkness; Goodbye, lively brightness of our too-brief summers!

Here is my translation of Apollinaire’s. For the first time, I’ve recorded a voiceover, thanks to a poet pal who told me I should, because poetry must be read aloud. And here is the original.

Apollinaire’s autumn is personified, and it is ailing. It is not well. One storm, one frost, will kill it. It is not the bursting, ripe cornucopia of Keats’s harvest moon. It is a late autumn, November turning to December, the moment you can feel the icy night air seeking something to coat in its crystalline velvet.

All that, I accept. What I cannot accept are these nixies in the second stanza.

Everything else in the poem is perfectly natural, perfectly normal. Coming storms? Check. Coming snow? Check. Ripeness? Rutting stags, ungathered fruit, leaf fall? Yes, yes, yes, yes.

So what’s with these nixies?

Nixies (as I explain briefly in my footnote) are mythical river spirits from German folklore. Exactly like their briny counterparts, the mermaids, they lure people into the water to drown. Their most famous member is the Lorelei. Nasty creatures! So there they are, combing their long green hair, while sparrowhawks hover above. Why are they there? They don’t seem particularly autumnal.

This was one of the poems Apollinaire wrote that fateful year in Germany, when he fell in love with Annie as they loitered along the Rhine. One of the words for nixies in German is Rheintöchter, literally Rhine daughters, though generally translated as Rhine maidens. They feature in Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle of operas, beginning with Das Rheingold. There they are creatures of silly simplicity, set to guard a hoard of gold, but pretty careless about the job, because only someone who renounces love forever can steal it. They think the dwarf Alberich is in love with them, so they ignore his hankering for it. But he wants it more than he wants them, and he does make off with it.

The word “dwarf” appears in a feminine, plural form in the poem, so it reads as an oblique reference to Wagner’s Rhine maidens; the nixiness and dwarfishness are all commingled. In general, though, mermaids are thick in the water in Apollinaire. See “The Song of the Unloved” for an absolute pod of mermaids: the speaker knows songs for mermaids, a swan dies in a mermaid way, and there are even mermaids swimming in his beloved’s eyes. Perhaps he saw Annie as a sort of Lorelei, luring him to some doom.

At any rate, the nixies are here probably because they have to do with enchantment and lovelessness and Germany. They also lend what otherwise would be a standard bucolic poem of autumn in the countryside an air of myth and mysticism, as well as erudition, which Apollinaire can never resist.

As for why publish this when it is nearly May, look. I’m in England. It is still cold, damp and gray. England’s spring is a sick spring. So my wintry thoughts persist, no matter what the calendar pretends. Wake me when it’s summer.

I am annotating and translating Apollinaire as I go, making the poems and my commentary free to read. If you’d like to support me, your free subscription encourages me. A paid subscription will buy me a bag of coffee, the fuel of literature. And share it with a poetry-besotted friend. Thank you for reading!

Autumn Day

Going out, those bold days,

O what a gallery-roar of trees and gale-wash

Of leaves abashed me, what a shudder and shore

Of bladdery shadows dashed on windows ablaze,

What hedge-shingle seething, what vast lime-splashes

Of light clouting the land. Never had I seen

Such a running over of clover, such tissue sheets

Of cloud poled asunder by sun, such plunges

And thunder-load of fun. Trees, grasses, wings - all

On a hone of wind sluiced and sleeked one way,

Smooth and close as the pile of a pony's coat,

But, in a moment, smoke-slewed, glared, squinted back

And up like sticking bones shockingly unkinned.

How my heart, like all these, was silk and thistle

By turns, how it fitted and followed the stiff lifts

And easy falls of them, or, like that bird above me,

No longer crushing against cushions of air,

Hung in happy apathy, waiting for wind-rifts:

Who could not dance on, and be dandled by, such a day

Of loud expansion? when every flash and shout

Took the hook of the mind and reeled out the eye's line

Into whips and whirl-spools of light, when every ash-shoot shone

Like a weal and was gone in the gloom of the wind's lash.

Who could not feel it? the uplift and total subtraction

Of breath as, now bellying, now in abeyance,

The gust poured up from the camp's throat below, bringing

Garbled reports of guns and bugle-notes,

But, gullible, then drank them back again.

And I, dryly shuffling through the scurf of leaves

Fleeing like scuffled toast, was host to all these things;

In me were the spoon-swoops of wind, in me too

The rooks dying and settling like tea-leaves over the trees;

And, rumbling on rims of rhyme, mine were the haycarts home-creeping

Leaving the rough hedge-cheeks long-strawed and streaked with their weeping.

W.R. Rodgers

deep autumn

my neighbor

how does he live, I wonder.

Basho